|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

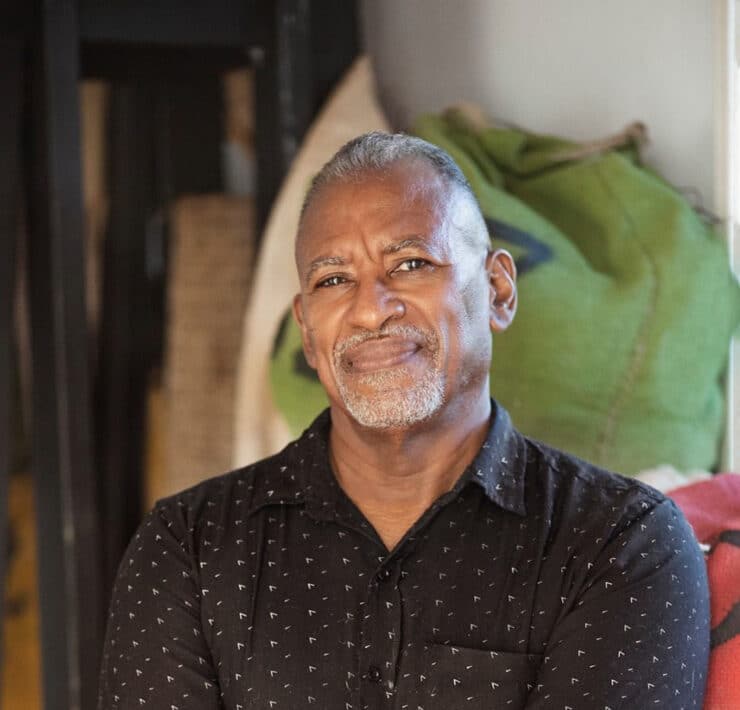

Shaun Leonardo’s multidisciplinary work is inexorably tied up with experience—his experiences as an activist and educator, the experiences of the communities in which he lives and works in New York City, and the experiences of participants in his workshops and performance art works.

But for Leonardo, the act of experiencing a space, memory, or feeling is simultaneously an opportunity to reflect, meditate, and explore. I sat down with him to discuss these intersections as well as the ideas and principles that underlie his work.

Can tell us a little bit about your upbringing and your connection to the arts? How did you decide you wanted to become an artist?

I am of Dominican and Guatemalan heritage. My mother’s from Santo Domingo; my father’s from La Ciudad de Guatemala. My parents, who are both now retired, worked in their respective fields for thirty to forty years. They really worked up the ladder in their careers: my mom having started as a secretary and culminating as the head of publishing in one of the departments at Simon and Schuster, [and] my father starting as a janitor and working his way up to supervise the entire laboratory at what was then called North Shore Hospital.

I attribute my work ethic to them. However, it was in the mentality of striving for the best that I was also taught that success meant economic stability and mobility. And so art wasn’t really within my vision as a child: I never quite know what inspired me, other than the moments where I did see and take in art. I don’t know what drove me to identify as an artist because it wasn’t within my familial background—not that I know of anyway—and my only exposure to art, growing up in Queens, were the moments here and there where we visited the Queens Museum and the Metropolitan Museum.

But you did arrive to a point where you validated yourself as an artist?

Most important, I think, was whenever I saw a master, codified “master,” at the Metropolitan Museum. Somehow, I [don’t] recall ever being dissuaded [by the fact] that those “masters” were all dead white men. I found myself seeing these “great artworks” and believing I could achieve that.

I do equate that stubbornness and conviction with the same work ethic that my parents filled me with, but to this day, I don’t understand how I never felt that the historical art canon could not be achieved simply because of my ethnicity or color. That was never a blockage for me, psychologically.

I’m glad, because I think it probably was intimidating for a lot of young minds.

Yes. I offer that narrative with the recognition that, over my life and professional career, I have witnessed young people be easily derailed when they don’t see themselves in the representation of who is creating.

Especially as I grew into my path as an educator, I found it equally important to share the work of my colleagues and those artists of color that inspired me with both young folks that I identified with (meaning those that looked like me) and white kids. For a white student, particularly a young white student, seeing the mode of expression of an artist of color can shift as much of their worldview as it does for a student of color.

I completely agree. And are you currently teaching, besides your professional practice?

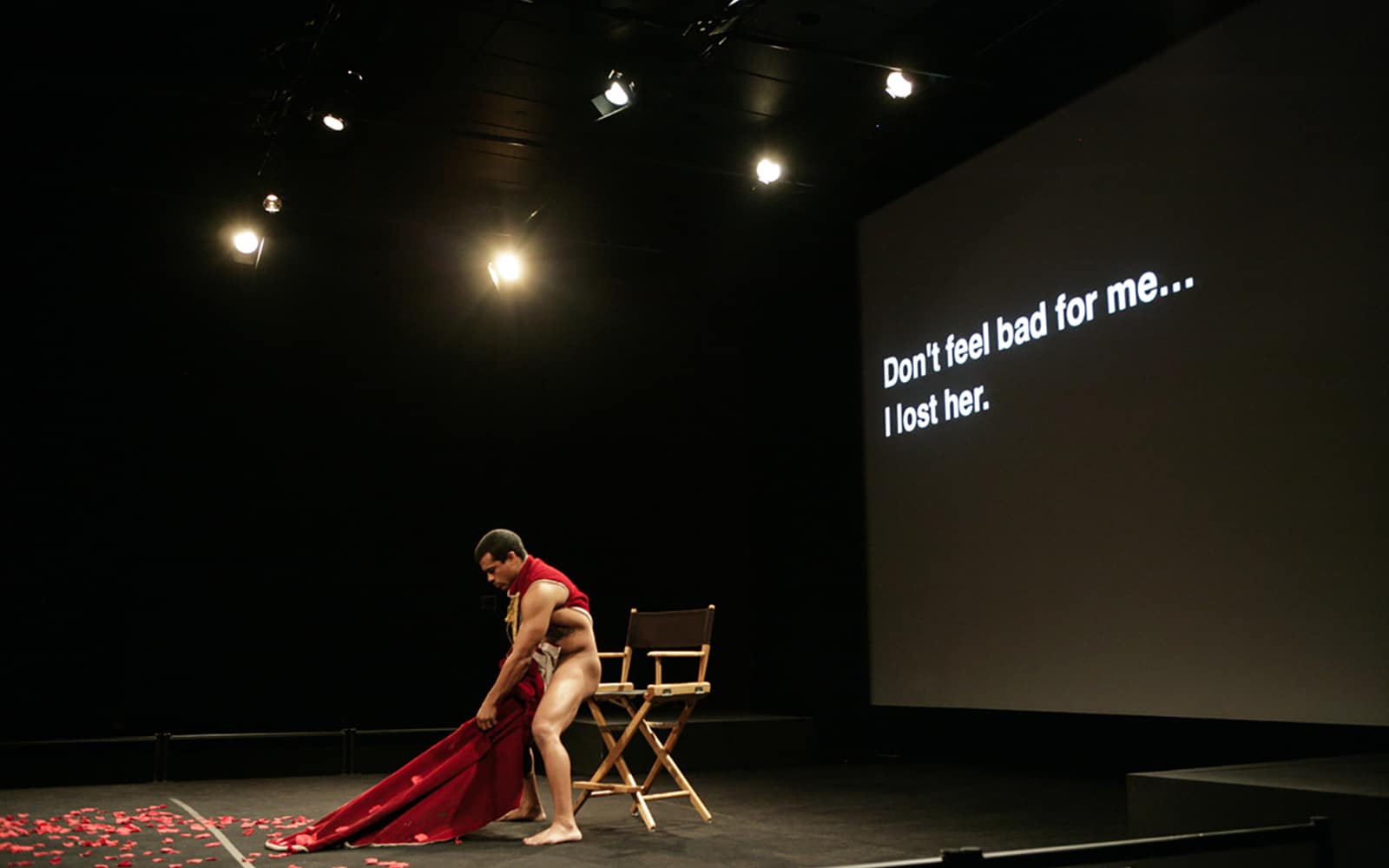

I don’t, and I haven’t for a long while, created a distinction between the two. I am now the codirector of Recess, a nonprofit art organization that is centered on socially engaged practice and even more centered on practices that engage topics of social justice. This is the same organization within which I cofounded the Assembly Diversion Program, which works in conjunction with the criminal court here in Brooklyn.

That practice takes the form of a workshop, as does much of my performance. So it is difficult for me to distinguish what others might call a more “polished performance” from a pedagogical practice because for me, they’re one and the same. The workshop, the platform of teaching and learning, is in and of itself the performance. It doesn’t lead to another output or product.

Can you talk about some of your latest projects?

There are two consecutive projects that both uniquely provided a very new invitation to my holistic practice. One, which is at MASS MoCA [the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art], will be [in place] for two years. And another is about to premiere as a large public artwork commission at Four Freedoms Park on Roosevelt Island.

What is central to both of those opportunities is that the institutions were asking me to develop a physical project installation informed by my performance work. At MASS MoCA, the invitation was to see a hallway that would otherwise be overlooked as a passage that invites a stillness, a contemplativeness of memory and also of one’s own subtle movements. That project is entitled “You Walk”: as guests pass through this hallway, they encounter different text prompts that invite them to slow down. In the poetics of the text, I’m asking an individual to not only create their own associations with their lived experience but also imagine that same movement embodied by a very different person.

That is echoed by visual elements in the space: the windows on one side are obscured by mirrors, so you continuously see your own image as you pass through and take in these prompts. Opposite each of the actual windows is a fake window that duplicates exactly what you might see to your left but with one element slightly askew. So you’re presented with two realities of the same location, one which notes where you actually are and then a limited window that gives you the possibility of seeing that same present tense in a different context.

And the Roosevelt Island Project?

Four Freedoms Park Conservancy is a memorial to Franklin Delano Roosevelt and specifically to his speech concerning the four freedoms: freedom from want, freedom from fear, freedom of speech, and freedom of worship.

Over a year and a half ago, the park and I were contemplating a large-scale performance work, which was abruptly shut down by COVID. The conversation evolved into the possibility of two monumental “murals,” which are not paint but vinyl: they are emblazoned on the two facades of the park and are viewable from across the river in both Queens and Manhattan.

Those images will be static hand gestures, all generated by a performance-based workshop process with community members that self-identified as vulnerable when contemplating, or in the face of, those four freedoms. Through this workshop process, we looked at what a contemporary reinterpretation of those freedoms could be through the lives of those community members. And the result was a series of narratives where these participants spoke about how they believed freedom was afforded, or not, but also about the ways in which we embody those narratives.

What I honed in on is what the community members did with their hands when expressing those stories. Those static murals can be activated on one’s phone into these beautiful animations that slowly morph those gestures into others. And as you’re witnessing that movement, you hear one of the participants speak about a freedom. And all of that material was extracted from the workshop process, a process that would in the past otherwise go entirely invisible.

Can you speak to the challenges of our new normal and how they have affected your practice?

I think the larger challenge surrounding not only the pandemic but also the converging crises of racial justice, reproductive rights, and everything else is the immediacy with which we are being called upon to act. This is infiltrated and influenced by social media and the sort of commotion and chaos of the news cycle: we feel compelled to act, act, act—to respond, respond, respond—and artists don’t operate best in that rhythm. Artists need to take in, to process, to decipher, to separate from the noise and create things that are beautiful and impactful to the spirit. Artists have to offer a different type of slowness to work against the speed of today.

Puerto Rican born, Edra Soto is an interdisciplinary artist and codirector of the outdoor project space the Franklin.

Recent venues presenting Soto’s work include Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art’s satellite, the Momentary (Arkansas); Albright-Knox Northland (New York); Chicago Cultural Center (Illinois); Smart Museum (Illinois); and the Museum of Contemporary Photography (Illinois).

Recently, Soto completed the public art commission titled Screenhouse, which is currently at Millennium Park. Soto has attended residency programs at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Beta-Local, the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Residency, the Headlands Center for the Arts, Project Row Houses, and Art Omi, among others. Soto was awarded the Efroymson Contemporary Arts Fellowship, the Illinois Arts Council Agency Fellowship, the inaugural Foundwork Artist Prize, and the Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grant, among others. Between 2019-2020, Soto exhibited and traveled to Brazil, Puerto Rico, and Cuba as part of the MacArthur Foundation’s International Connections Fund.

Soto holds an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a bachelor’s degree from Escuela de Artes Plásticas y Diseño de Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rican born, Edra Soto is an interdisciplinary artist and codirector of the outdoor project space the Franklin. Soto has been awarded the Efroymson Contemporary Arts Fellowship, the Illinois Arts Council Agency Fellowship, the inaugural Foundwork Artist Prize, and the Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grant, among others.