|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

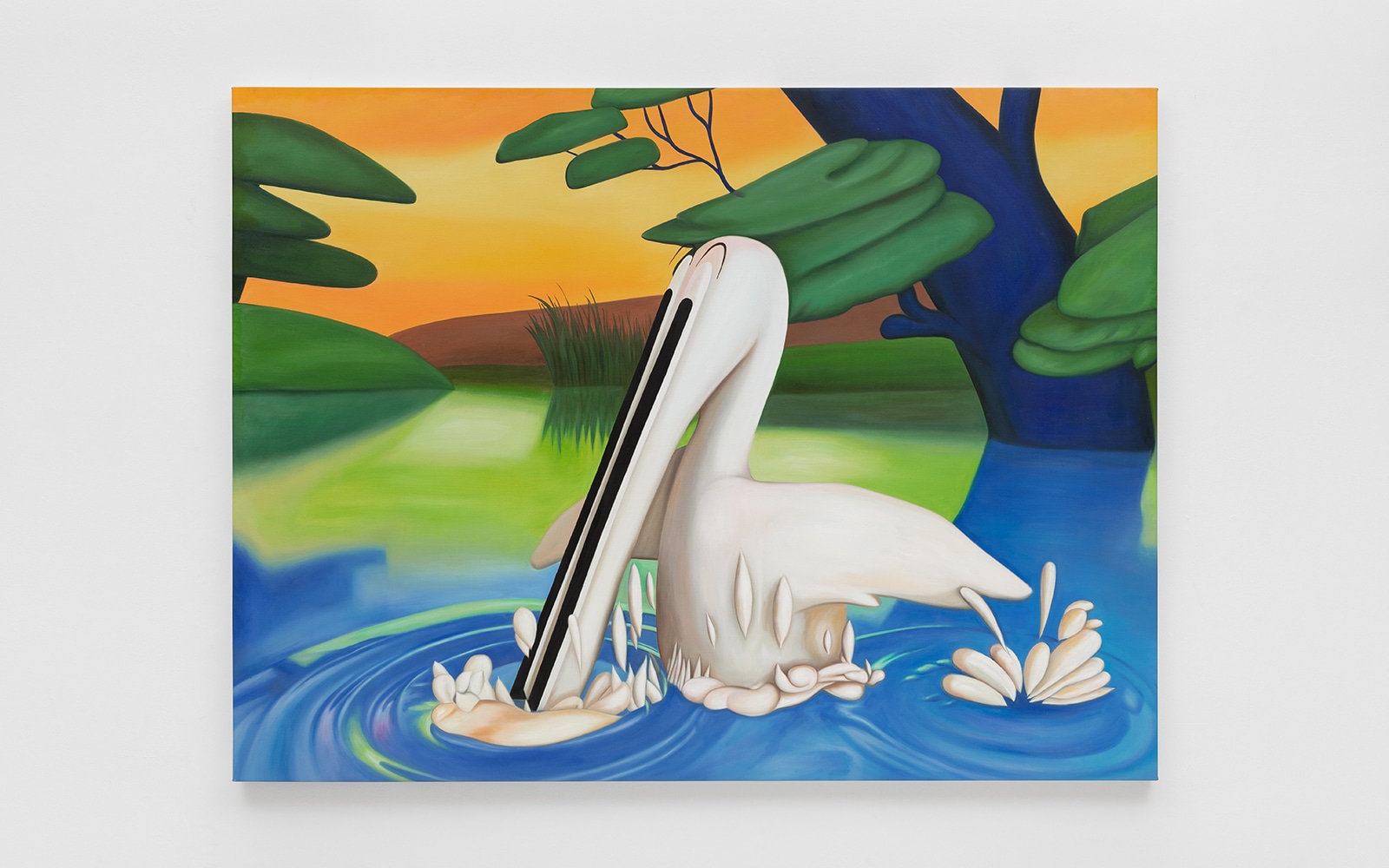

Edgar Serrano has made a name for himself by making the invisible visible. Borders, transitions, subliminal spaces and concepts—his work makes space for, and celebrates, that which we cannot see by looking at it straight on. I sat down with the Mexican American painter and Chicago native to discuss the ways in which his work captures our hybrid physical-virtual reality and the hidden moments that speak truth to our transition between those types of in-between spaces.

Please tell us about your upbringing and how it impacted your decision to become a visual artist.

I didn’t encounter many paintings growing up. Due to my parents’ lack of education and interest in high art or culture, the images that populated my childhood were reproductions and cartoons. Through a series of fortuitous events, guidance from some wonderful people, and stubborn perseverance, I enrolled at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago on a full presidential merit scholarship. While there, however, I felt uncomfortable in the museum. Instead of standing in front of paintings as instructed by my professors, I bought postcards from the gift shop and wrote my art history papers from these reproductions. Despite what Walter Benjamin would have had me believe, these cheaply printed mass-produced images still carried their aura.

After I graduated, I felt like it was nice to go to art school, like a vacation or holiday. It was my first time being around an art community, art students and teachers, so that was all new and exciting. But I felt like it wasn’t the real world. So, I took a year off from art and just worked—but I realized I missed the plush art bubble, and so I applied for graduate school. I applied to Yale and was fortunate enough to get accepted. Being an artist seemed like an easier and perhaps healthier choice than running aimlessly in the streets of Chicago.

Cartoon references and reproductions are abundant in your visual practice. How do these images enter your visual world and manifest in your life? What do they mean to you?

The way cartoons manifested themselves in my life again was during the Trump administration. Images of migrant children in cages in the New York Times had a really profound effect on me. I’m a father now: looking at these young children reminded me of my son and family, and of myself coming to the US not knowing English. I was really captivated by these images; they stirred up a lot of emotions. There was one of a little boy, alone and surrounded by guards, looking up at a cartoon, Casper the Friendly Ghost. I think that really resonated with me. The child and cartoon were both in this state of flux, in limbo. That’s what stirred this whole thing, seeing that little boy looking at cartoons, and at the ghost that mirrored his own situation of being caught between two political realities.

Recently I’ve been interested in hand-drawn animation smears, which depict one quick blur of motion in a single frame, and the illusion of movement found in cartoons from the 1920s to 1960s, the golden age of American animation. These in-between movements mirrored my own childhood of being the son of immigrants and not knowing English, the blur acting as a state of being caught in-between two realities. My relationship to these images is symbolic and contains a dark narrative subtext.

All paintings in this series were excavated from various childhood cartoon sources using old VHS tapes that were converted to digital files and then edited using digital video editing software. Using digital video editing software, I can analyze video files frame-by-frame, isolating and excavating normally invisible moments of transition or blur. Resulting images are both familiar and strange, showing well-known cartoon characters in states of transition usually undetectable to the human eye due to the durational speed of each frame.

These experiences with cartoons and reproductions helped me form my own way of seeing and making art. My quest—personal and artistic—is to unearth invisible states and identities. Fixed categories of identity can be used to marginalize, but they can also be used by the marginalized to gain visibility and political power. This paradox is the central focus of my practice.

I enjoy the relationship between popular culture and philosophy in your practice. Please, tell us when and how this relationship started becoming evident in your painting and who inspires these connections.

I employ the concept of theblur as an idea that broadly represents in-between places, both physically and psychologically, as well as the “between” of recognizable and unrecognizable shape-shifting forms. My paintings situate the viewer on an unlikely border between the familiar and the indecipherable. According to the eighteenth century German philosopher Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, the longer one looks at any frozen momentary action, the more unnatural and grotesque it appears. That is precisely what these paintings represent, showing the terror-filled, frozen moment of our current political reality.

Most of my source cartoons come from a time of immense turbulence in the world, including World War II. There’s this search for a better world in the strange landscapes that populate some of these paintings that I’ve manipulated—increasing the saturation, altering the color—but I’m not really looking for a utopian ideal. I see utopia as a lot darker or more toxic. I’m always suspicious of images that try to manipulate me to feel serene. Immediately, my alarms go off at this manufactured serenity. I try to show a darker side of these paintings. It’s a strange thing, looking at paintings when you can’t really categorize the grotesque, uncanny images they contain. You’re perpetually waiting for it to return to its original form, but as it’s a painting, it’s permanently in this state of transition.

Lessing further argued that paintings should represent “a single moment of action,” and this single moment “must express nothing transitory.” He was completely against moments of transition or intense transitory emotion, like ecstasy or pain. The desire for these static in-between paintings to revert to an original or recognizable form is the hope for a return to normalcy, which perhaps is the biggest illusion.

You refer to borders in a metaphorical and literal manner through your practice. What experiences prompted you to engage with the concept of borders?

We live in a hybrid reality—part physical, part virtual. These are two different but not entirely separate worlds, their borders continually dissolving and reforming. I know this borderland well. I am the child of Mexican immigrants, and I have lived my entire life along unseen but ever-present borders. Likewise, my paintings negotiate literal and figurative divisions and situate the viewer on unlikely boundaries between the digital and the real, the alien and the familiar.

Take my recent work, which engages with animation smears. While the cartoon characters may be familiar, these in-between moments were never intended to be seen due to the speed of the film and the short duration of the transitions. The blur visually embodies in-between spaces and changing psychological states. These blurred images from the cartoons of my childhood mirror the trauma of transitioning to American culture, the struggle to process and internalize countless visible codes and invisible rules, and more generally, the position of undocumented immigrants stuck in a permanent in-between state, legally, culturally, and linguistically. It is this transition that I want to make visible.

What are your thoughts regarding Latino artists’ increasing visibility in the art world?

I think it is essential as humans, as a culture, and a community to be open to different perspectives. Otherwise, there is no growth, just stagnation, repetition, and regurgitation of the same basic ideas. That’s boring. That’s so 2014.

I am obviously a champion for Latinx artists’ visibility in the art world, along with every other marginalized group whose voice needs to be heard and contended with. There is enough room at the table for everyone—if not, we need a new table.

The conflict, chaos, violence, and confusion that your paintings express are reminiscent of our current political climate. What makes art and artists so essential to our society?

I use reproductions and cartoons to make art that is hopefully democratic and accessible. The American cartoons I mentioned earlier were all hand-drawn and hand-painted, and their soundtracks mostly featured classical music and no real dialogue. So, it was kind of a universal language, like slapstick comedy or the Fast and the Furious franchise.

Their movements and moments were haunting and reflective of our current political realities, but also open. I don’t want to make work that’s really didactic, overtly political, or anything like that because it’s just kind of a closed circuit. I am more interested in moments that we weren’t meant to see. Invisible moments or unnamable moments. Maybe there’s a different reality, a more traumatic way of looking at these images? For me, it’s really born out of direct representation and personal context.

I think artists digest and process information differently, which results, in my case, in some strange yet familiar paintings with embedded metadata from our times. Perhaps we speak truths in way that is made palatable through the eyes and brain. I only know that I enjoy looking and thinking about art most of the time. Most of my friends are artists, and I can’t imagine living without them.

What media are you currently consuming?

I am reading Civilizations: A Novel by Laurent Binet which asks, what if history had been different? What if Columbus had failed? What if the Incas had invaded Europe and prevailed? The book is satirical and playful, and poses serious questions about tolerance and the role of government.

I’m also listening to audiobooks like The Twilight World, written and narrated by Werner Herzog, as a form of sleep aid and learning through osmosis. It is such a great book! I fall asleep to Herzog whispering a story in my ear every night. I don’t know much about the book besides that it is the story of Hiroo Onoda, a Japanese soldier who defended a small island in the Philippines for twenty-nine years after the end of World War II. So, I guess my attempt to learn through osmosis is a failure. But I’ve never slept better.