|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Chicago-based interdisciplinary artist Moises Salazar addresses queer and immigrant bodies as a vehicle to celebrate cultural heritage and reflect on histories of trauma. Raised by immigrant parents, Salazar has learned firsthand about the instability of living in the United States and how one’s identity can both challenge their rights as a citizen and constantly jeopardize their safety.

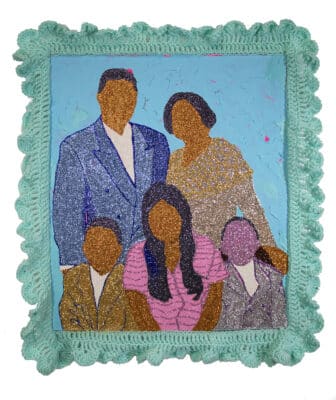

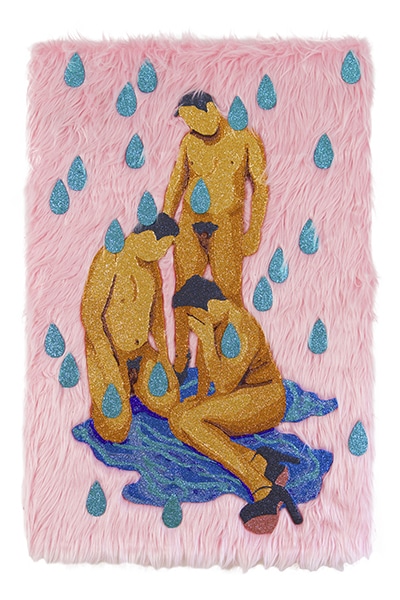

Deceptively festive and packed with passive pastel colors, his collages and sculptural installations are layered with a profoundly personal approach to the representations of the immigrant bodies he conveys.

As a nonbinary queer artist, Salazar draws parallels between the immigrant identity and that of race, gender, queerness ethnicity, intersectionality, and notions of nationalism.

An admirer of Salazar’s work, I sat down with him to discuss the meaning that his work holds both on a personal level and for the Hispanic community at large.

What made you decide to be an artist?

I finally trust myself. I have always known that I naturally have inclinations to create, but making art and becoming a working artist are two slightly different things. About three years ago, after some success, I finally trusted that this is something that I have to do—not just make art but become a working artist. With the support of my family, I have been able to dedicate myself to my practice.

Maintaining my practice is so important to me because it’s the way I can connect with people within the groups I am a part of and build relationships with other working artists and creatives. I also believe that I represent a very specific experience and that it’s my responsibility to create work that speaks on those experiences for the sake of representation and to spark change.

Your relationship with your family seems to be very influential on your practice. How does this relationship filter into your work?

I consider myself lucky. I had the privilege of living with my family all my life. They formed an integral part of my upbringing, so it feels very natural to be influenced by my relationship with them. I like to think I make work about my family because I am still processing certain parts of my life. I reflect on the best moments and the worst. I also use materials and techniques that have been passed down from my family to me. Crochet, ceramics, paper-mache, and sewing are some of the things that I have been taught by family members, and these techniques have become the main focus of my practice.

Can you talk about your relationship to activism?

My parents taught me that everyone does their part to better our society. They explained that there are those who educate, those who provide resources, those who take up space, and those who organize with the aim of creating positive change in our community. I understood that it’s my responsibility to figure out what I can provide and share it with those who are in need.

At this moment in my life, I have chosen to use my platform to create representation and become an art educator. By making work about queer and immigrant issues, I wish to educate people outside of those communities about the harsh reality these groups face. At the same time, I am a part of a couple of art educational institutions that I morally identify with. I try to always share my resources with young artists to continue the stream of mentorship. I have the privilege to have been accepted by the art world, and I now stand in the threshold of the entrance. It is my duty to hold the door open to let my community inside.

The body plays a primary role in your work. How would you describe some of the meanings contained in your extraordinarily moving figures?

The truth is, the majority of my glitter paintings in Brillo Putx are self-portraits and have become influenced by my experience. That could range from making a painting reflecting on a bad breakup to creating a painting because I bought a new eye-shadow palette. My paintings have become a type of diary where I can document parts of my life and create a space where I can mourn or express my relationships with sadness, loneliness, and disappointment. I allow my figures to process emotions and events in my life that I still haven’t even addressed.

In Cuerpo Desechables, the bodies I represent are immigrant bodies in detention centers. They are installed in a way that is representative of the poor living conditions people face when they are detained. I chose to represent children because of the surge of unaccompanied minors found at the border. Universally, we accept that children are innocent and that we have a moral obligation to protect them, yet they are treated as criminals and left to suffer in our detention centers.

There’s a coexisting relationship between queerness and immigration in your work. How does that relationship manifest, metaphorically and/or physically?

I often find similarities between queer and immigrant communities. I participate in both by being queer and by having immigrant lineage. I have seen how both communities are able to shape-shift and create resources with the aim of not only surviving but thriving. I see the parallels between the way that my mom calls my tía to see if she knows someone trustworthy that can change her car oil for cheap and the way that I myself ask for and give advice on what organizations to go to for HIV testing, no questions asked. Trust and word of mouth is a powerful currency that both of these communities rely on.

I am fascinated by those relationships, and I just become obsessed with them. These relationships manifest physically in my work through representations of the extravagance and glamour that is integral to the celebration rituals of both communities. I use glitter, satin, faux fur, crochet, clay, and paper-mache because these materials are accessible to both groups.

Who or what is currently inspiring and influencing your practice?

I have been reflecting on how to activate my practice with performance. I have been watching everything from performances by chinelos to video content made by drag queens. Chinelos are dancers dressed in a traditional custom that originally came from Morelos, but the performance style has spread around many parts of Mexico including Puebla, which is where my parents are from. I often saw them at festivals here in Chicago, and recently have been interested in responding to the performance’s history and my relationship to seeing them as a child. I also have been seeing a lot of content made by established drag queens, such as Bob the Drag Queen, Peppermint, and Monét X Change: it has helped bring humor and glamour into my life during the quarantine. It also inspires me to find ways to introduce drag into my practice. In general, performing has been on my mind.

Puerto Rican born, Edra Soto is an interdisciplinary artist and codirector of the outdoor project space, the Franklin.

Recent venues presenting Soto’s work include Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art’s satellite, the Momentary (Arkansas); Albright-Knox Northland (New York); Chicago Cultural Center (Illinois); Smart Museum (Illinois); and the Museum of Contemporary Photography (Illinois).

Recently, Soto completed the public art commission titled Screenhouse, which is currently at Millennium Park. Soto has attended residency programs at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Beta-Local, the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Residency, the Headlands Center for the Arts, Project Row Houses, and Art Omi, among others. Soto was awarded the Efroymson Contemporary Arts Fellowship, the Illinois Arts Council Agency Fellowship, the inaugural Foundwork Artist Prize, and the Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grant, among others. Between 2019-2020, Soto exhibited and traveled to Brazil, Puerto Rico, and Cuba as part of the MacArthur Foundation’s International Connections Fund.

Soto holds an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a bachelor’s degree from Escuela de Artes Plásticas y Diseño de Puerto Rico.