|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Memory transports me back to September 2012. I am hovering over a salad bar in a hotel restaurant in Charlotte, North Carolina. Across from me, on the other side of the sliced bell pepper, is a friend of mine who is having a moment.

I tell my friend that one of his best attributes is that—unlike most politicians—he lacks swagger. I say to him that there are plenty of folks I’ve covered over the years who have done less but brag more.

He smiles and shrugs, explaining that a humble upbringing keeps him grounded. He was taught—by his mother and by circumstance—not to think less of himself but also not to think himself above anyone else.

Later that night, in an event that CNN has sent me to write about, the Mexican American political superstar who grew up on the hardscrabble west side of San Antonio and worked his tail off to one day breathe rarified air will walk into the Time Warner Cable Arena and deliver what his young daughter is calling “Daddy’s big speech.”

The speech is the keynote address at the 2012 Democratic Convention (which will, in a few days, nominate Barack Obama for another term as president). What makes it big is that the 2004 convention’s keynote speech, given by Obama when he was an Illinois state lawmaker running for the US Senate, was what put Obama on the map politically.

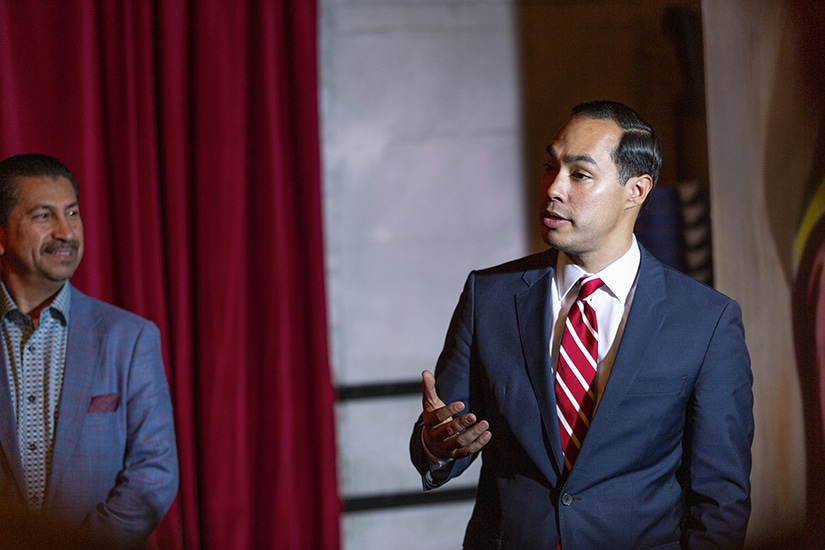

And “Daddy” is Julián Castro, who was at that point the mayor of San Antonio. Though there is a feeling among the family and friends who traveled from Texas that his career trajectory could change tonight.

It did. After being introduced by his twin brother, Joaquin, a US Representative from San Antonio, Castro took the podium. He crushed the speech. He was comfortable and fiery, self-deprecating and likable, humorous but sure of his convictions.

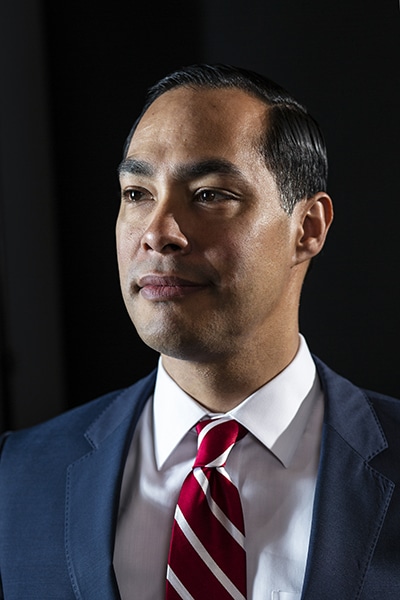

Over the next seven years, Castro’s résumé would grow to include a stint as secretary of Housing and Urban Development, a book deal to write a memoir, a string of speeches around the country, a teaching gig at the University of Texas at Austin—and, now, at forty-four years old (turning forty-five on September 16), a historic pursuit that also amounts to his toughest challenge.

Tough enough for people to ask: Does Castro really want to win this thing?

“This thing,” of course, being the Democratic nomination in the 2020 US presidential election.

And Castro being a serious, credible, and highly electable public official vying to be the first Mexican-American president in our nation’s history.

Running for president isn’t a policy seminar or a spelling bee. It’s performance art. Voters buy their ticket, and they demand a show.

During a recent swing through California, I caught up with my friend and asked him: “What’s the Julián show?”

“There’s always a showmanship to politics,” he acknowledged. “I grew up watching Ronald Reagan, disagreeing completely with his politics but recognizing that he was a showman in his own right. And then Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, Donald Trump—all of them have, in their own way, been master performers. The question is not whether you have to perform in politics, it’s what kind of show do people want right now?”

“And? What kind of show is that?” I asked.

“This campaign is a counter to Trump’s show,” he said. “I’m convinced with this election people want the opposite of Donald Trump. That’s not to say they want somebody who’s completely dry and boring, but they want somebody who’s level-headed, who is inclusive, who is honest, who is focused on the future instead of the past and is trying to bring people together instead of tearing them apart. That’s the show that I’m going to give them.”

Another thing that voters want to see in a candidate is gravitas, the quality that reassures them that he or she is ready to lead the country on day one.

I asked Castro how candidates demonstrate gravitas.

“Different ways: command of the issues, the way they treat people, how they are on the campaign trail and [how they] answer questions,” he said. “And, of course, their experience also plays a big role in that. For me, I have plenty of experience at the local level and also at the federal level, I’ve shown a command of the issues ranging from domestic issues to foreign policy issues. So I believe that, when the debates start, people are going to be able to see me as a compelling candidate.”

“This an executive position. [US presidents] have to be confident, effective executives who realize that their role is to set a strong, bold vision, to hold people working for you accountable to achieve that vision. You have to remember that you are only one of three branches. The best presidents understood that.”

Of course, voters also crave good leadership.

I asked Castro to name what he thought were the leadership qualities required to become president.

“First, the ability to move people, to inspire people to change goals, whether that was Franklin Roosevelt or Lyndon Johnson—or on the other side of the aisle, in his own way, Ronald Reagan,” he said. “Good leaders can inspire people. They lay out a vision that the majority of Americans can believe in.”

“Second, they’re confident,” he continued. “This an executive position. They have to be confident, effective executives who realize that their role is to set a strong, bold vision, to hold people working for you accountable to achieve that vision. You have to remember that you are only one of three branches. The best presidents understood that.”

And he saved the most important leadership trait for last.

“Then third, I would say that that good leaders are people who everyday Americans can relate to,” he said. “That’s how they’re successful in the first place. They can’t be too high-minded or out of touch.”

Then I asked Castro about his own leadership philosophy, which I presumed helped guide him while serving in the Cabinet.

He summarized it as: “Bold vision, strong team, and accountability on execution.”

Also, I wondered, how does he go about choosing his team?

“I look for people who treat other people with respect,” he said. “I look for an inclusive team because I appreciate diverse perspectives—people coming to issues and problem solving from different angles, so to speak. I look for people who work hard, who have a strong work ethic so that you don’t have to wonder whether they’re going to get the job done.”

And how has that strategy worked out in the past?

“I’ve been fortunate—both when I was mayor and when I was HUD secretary—that we had a lot people that were hardworking or respectful and brought fantastic ideas to share so that we could accomplish good things for the people that we served,” he said.

So back to the big question: does Castro really want to win this thing?

I wondered about that myself. And so I asked him point-blank.

“The results I’ve gotten in public service show that I want to do good for people,” Castro replied. “I wouldn’t put myself through this crazy process, in this day and age—wouldn’t run the gauntlet and put up with everything from a million different criticisms to Twitter trolls to outright lies about you as a person—unless I had a great passion for making a difference in this country.”

But, I pressed him, what about those who think he lacks the fire necessary to get elected?

“I’m not the loudest candidate or the loudest personality,” he acknowledged. “But I’ve shown a fire consistently over the years to make a big difference for people. And I believe that’s what counts and that’s what’s going to get us through this campaign.”

In the end, most of the reporters who cover Castro in this campaign won’t understand him. And so they won’t understand how he can win—even by losing.

Look, I know he’d say that he is “in it to win it.”

For one thing, he has to say that. He needs to raise millions of dollars to simply remain competitive in an enormously crowded field of Democratic hopefuls—all of them itching for the chance to run against Trump in the general election. You can’t convince people to part with their money if they think you’re not 1,000 percent committed to winning the nomination.

Then again, maybe Castro actually means it. Maybe he is playing this game to win, and maybe he’s prepared to engage in the unpleasantries necessary to win—which include attacking fellow Democrats who will not hesitate to return the favor or perhaps attack first. After all, this is a guy who has spent his whole life, from high school to Stanford University to Harvard Law School, knowing the answers to the quiz. He doesn’t try for second place at anything he does.

Castro has skills. He has always been serious about creating for others the kinds of opportunities that he and his brother have enjoyed. He doesn’t strut or overpromise. He gets the job done.

Think about what the striver tells young people whenever he speaks at a college or university.

“I always tell them that the most important thing is to believe in yourself,” he said. “There are so many things in this world. It doesn’t matter who you are, you will encounter things that pull you down or try to pull you backward. And in order to succeed, you have to have a strong confidence and belief in yourself. Second, to surround yourself with people who believe in you. And third, to always reach for a little bit more than you think you can get.”

Confidence is fine. Reaching is good. But, in his current endeavor, Castro faces long odds. He got off to slow start, spending the early weeks of the campaign ignored by media and stuck at 1 percent in the polls.

Plus, running for president is always tough. The hours, the fundraising, the promises; it can be too much for many to handle. But running as a Mexican American in a country whose coloring book doesn’t extend beyond black and white—this goes beyond tough. It can be nearly impossible.

Running for president is always tough. But running as a Mexican American in a country whose coloring book doesn’t extend beyond black and white—this goes beyond tough. It can be nearly impossible.

And then, in the case of the 2020 election, impossible got even more difficult when the Democratic Party drifted to the left on taxes, abortion, reparations, Medicare for all, immigration, and more.

Castro went with the flow and drifted with the party.

But here’s the problem: that’s not him. Just as importantly, that’s not where Mexican Americans are. Sure, we overwhelmingly register as Democrats. However, we’re a Catholic, center-right community which is more likely to, according to decades of surveys, call ourselves “conservative” than “liberal.” So you could say that the shepherd has strayed from his flock.

Still, I can see a path where he wins—even if he loses.

Here’s what I mean by that: He has already moved the football from where it was—from where Henry Cisneros, the other former San Antonio mayor who went on to become HUD secretary, left it. If Castro runs a strong, decent, and dignified campaign, and makes it past Super Tuesday—March 3, 2020, when more than ten states will hold primaries including vote-rich California and Texas—it’ll be a win.

Anything that happens after that is gravy.

Maybe, as the field narrows, he’ll run out of money and have to drop out. And then maybe, having already been vetted, he’ll get tapped to be on the Democratic ticket alongside the nominee. Who knows?

Still, no matter how things go from here, no one will fault Castro for not being able to do the impossible. Rather, millions of Americans will credit him for climbing into the arena, putting up a good fight and—here’s where the “win” comes—making the road smoother for whomever comes next.

In my book—and, I would venture to say, in most books—that’s a win.

It’s also the makings of a great story. The first chapter was penned that night in Charlotte back in 2012. And the last? Well, that one has yet to be written. It could be the most exciting of them all.

On Cultural Assimilation

“The good news is that, today, this youngest generation has to make the choice [of assimilating or staying true to their heritage] less and less. Today, it’s a plus in the business world—or just in general—to speak a second language like Spanish. You get paid more at your job if you speak Spanish oftentimes. In more and more public schools in our country, they’re teaching the history of the Latino community. Now Trump is a problem because he’s trying to take us backward. But aside from that, this youngest generation lives in world and in America where you don’t have to make that choice in the same way that my mother or my grandmother did or generations past.”—Julián Castro