When Sara Martinez Tucker arrived at her San Francisco home and her husband opened the door, she could tell he had been crying. When he told her she needed to call her parents in Laredo, Texas, she assumed the worst. Her father answered but was too close to tears to speak. Waiting on the other end of the line, Tucker’s fear grew. She heard her father choke out, “Mijito,” calling for her younger brother to take the phone. Bracing herself, she waited for the news no one seemed willing to break. “I think dad wants you to know,” her brother began, “that I just got my college degree.” At 37 years old, Tucker’s sibling became the last of three to finish college. Before the call could end, their father left Tucker with a final thought: “All my children are college graduates. I can die in peace now.”

Even if it were common for people from Tucker’s hometown to graduate from college, her father still may have cried at her brother’s accomplishment. Like all parents, he brought up his children with the hope that they would reach their potential. But unlike many parents—especially those who themselves never benefited from higher education—he refused to compromise on his children’s education. When he hung up the phone on the day his middle child fulfilled that commitment, Tucker realized just how exceptional her childhood was, and just how much she wanted to change that fact.

“I recognized how lucky I was to have parents that valued education,” Tucker says. “They sacrificed to send me to Catholic schools, which had better education, and supported my decision to leave Laredo. Too many people don’t have all those things lined up for them. I don’t want our kids to have to depend on luck to have success in life.”

Despite growing up in a low-income household and an environment where white-collar professionals were scarce, Tucker, who is CEO of the National Math + Science Initiative (NMSI), made the most of her parents’ sacrifices and more than “made it” professionally. Not many people can look back midway through their career and say they were the CEO of anything, or that they left such a high calling to pursue even greater things—like a presidential appointment. But, after nine years of funding college dreams as CEO of the Hispanic Scholarship Fund and then serving as under secretary of the Department of Education, Tucker decided to tackle the issue from another front.

“I went to Washington because one policy change can have implications for thousands of children,” she says. “But, unfortunately, education has become politicized. I have 46.7 million kids who can’t wait for that debate to get settled. They need help today.”

At NMSI, Tucker is taking the same no-compromises approach her father did. “We can’t rest while kids are in classrooms today without rigorous standards and high-quality teachers,” she says. “What gets me out of bed in the morning is getting kids the education they need to create the lives they want for themselves.”

The challenge NMSI faces is daunting, which makes the fight all the more urgent. “[Twenty] years ago, the US led the world in high school and college graduation rates,” states NMSI’s website. “Today, the US has dropped to ninth and seventh.” Two-thirds of American students are being taught math today by a teacher who didn’t study it. The figure is nearly 9 out of 10 for science. In some of the worst cases Tucker has seen, a school’s interpretation of a high school math class is teaching students to balance a checkbook. All these circumstances, under the guise of an equitable public education system, are particularly destructive for children of parents who, coming from countries where a high school education is the exception, assume the minimum education for a job with benefits is good enough. And that danger isn’t just a possibility; it’s already apparent in the lack of students studying science, technology, engineering, and/or math (STEM), let alone earning degrees in the fields.

Tucker refuses to be intimidated or adopt a defeatist attitude. NMSI’s programs are already in 28 states, and its college readiness program is in more than 550 high schools, up from 67 schools in 2009. In just one year of implementation, the NMSI program produces dramatic results: the average one-year increase in passing scores for AP math, science, and English exams in NMSI schools is 72 percent, 10 times the national average. Before the NMSI intervention, these schools had 16,481 passing exams; after just one year with NMSI, these schools had 28,274 passing exams. And after three years, the average increase in passing exams skyrockets to 144 percent.

NMSI achieves these results by removing barriers for teachers and schools and by implementing the following key elements of the program: more time on task for students, expert mentors for AP teachers, incentives for teachers and students based on success, and rigorous training for teachers—including the teachers in the middle schools that send students to these high schools. The program also supplies necessary equipment for the schools to teach AP classes and subsidizes half the cost of AP exams.

Participating schools are selected by NMSI based on factors such as demonstrated need, availability of funding—sometimes provided by a local company or an institution such as the Department of Defense—and above all, the administrators’ and teachers’ belief that “every student can learn and compete for rigorous education,” Tucker says.

Through its UTeach replication program, NMSI is expected to produce 18,000 new STEM teachers by 2025. Because UTeach teachers stay in the classroom longer—80 percent are still teaching after five years, compared to a national average of 54 percent—these 18,000 teachers will impact five million students.

The program represents a partnership within universities—35 to date across the country, with 10 more to be added in the next two years—between the colleges of natural sciences and colleges of education to transform the process of creating teachers and to emphasize content understanding. These universities recruit STEM teachers from top math and science majors early in their academic careers. To see if teaching is right for them, freshmen students are given the opportunity to experience public school teaching in well-supported environments.

The program’s graduates combine extensive content knowledge with research-based teaching strategies and project-based learning methods to ensure greater content mastery among their students. During their student-teaching experiences, the program’s participants receive personal attention and guidance from highly experienced K-12 master teachers.

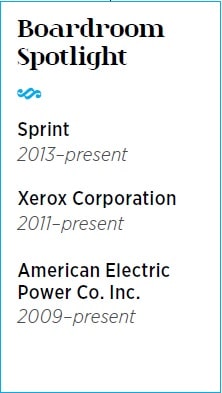

When Tucker left the government sector, she decided to take a more proactive, direct approach to improving education. But she realizes NMSI cannot reform the entire system alone. Through the corporate boards she sits on, she is privy to the changing needs in the workforce of the “knowledge economy,” as she calls it. And she also knows the importance of corporate partnerships, which is why NMSI submitted its two programs to the Business Roundtable’s call for identifying the country’s top K-12 programs. Both NMSI programs were named among the 10 finalists, and the UTeach program was one of the top five.

“Government funds many programs, and some aren’t producing outcomes,” Tucker says. “Absolutely NMSI needs help and partners, but not just anyone. We’ve got to focus on the programs that are making sustainable differences. I’m going to be rooting for all 10 of the Roundtable’s finalists to get funded and be successful.”

To get to know the other ‘Best of the Boardroom’ leaders, click here.