|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Currently roaming our solar system are what astrophysicists call “small bodies,” which include asteroids, trans-Neptunian objects, comets, and a category simply described as “transitional objects.” Those small bodies can be mere meters across, but some are thousands of kilometers wide—and about once a year an object the size of a washing machine enters the Earth’s atmosphere. Understanding that an asteroid did once wipe out about 95 percent of our species, and also noting that late physicist Stephen Hawking considered an asteroid collision to be earth’s biggest threat, it seems important, as a planet, to be aware.

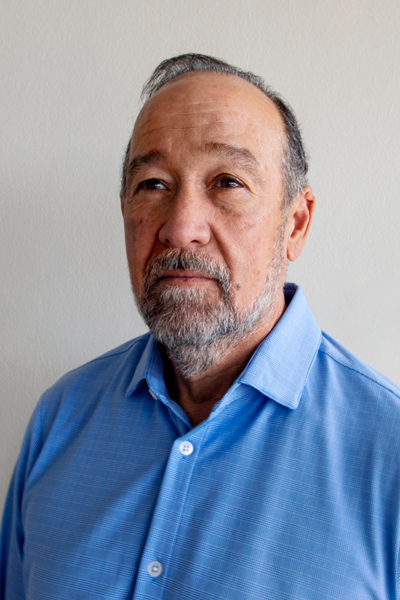

Fortunately, we’re not going about it blindly. The Florida Space Institute (FSI), a research facility created by the State University System of Florida and the University of Central Florida, is on the case. And since the arrival of Ramon “Ray” Lugo III in 2013 as the FSI director, the grants the Institute has secured for a variety of research and educational programs—as well as the study of small bodies—have quadrupled.

Lugo came to FSI with a made-for-this-job resume. He had previously served as director at the Glenn Research Center, charged with overall management and operations of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) facility. He has engineering and engineering management degrees, and he understands how to navigate the universe of government and university grant funding.

Because stopping those rogue chunks of space rocks is going to take some money and foresight. That’s what Lugo’s job is about, and he’s pretty clear that means recruiting the best and the brightest to make it happen.

“The idea is to create a research effort focused on space and space-related topics that are broader than what NASA does,” he says. The work of FSI goes far beyond the asteroid threat. It includes identifying commercial opportunities, the role of space in national defense, and being part of a consortium—with the University of Central Florida—that manages the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. Arecibo, built by Cornell University in the 1960s, is the largest fully operational radio telescope in the world.

“I decided I wanted to create something that would last beyond my tenure. Something that would help scientists, that would contribute to our understanding of science and space.”

On the way to becoming the leader at FSI, Lugo had gone into something of a retirement mind-set. He was initially in conversation with the Institute’s governance committee about an advisory board position, but becoming the director began to make more sense.

“We were only lightly funded at the time and there were no students on site,” he says. “I decided I wanted to create something that would last beyond my tenure. Something that would help scientists, that would contribute to our understanding of science and space.”

Lugo’s first steps were to bring in PhDs and postdoctoral scientists to attract grant funding. FSI receives $800,000 annually from the Florida state legislature for seed funding, but currently has more than $10 million from external sources happy to recognize the value of what the Institute’s scientists are doing.

That includes the development and actual manufacturing of regolith—the dust, rocks, and soil that are found on extraterrestrial bodies, including the moon. FSI is a repository of the physical and chemical makeup of this “moon dust” (and that of Mars, Jupiter, asteroids, etc), and with more than two hundred companies for customers, it is able to recover costs involved in producing it. Lugo says that government space agencies and corporations use the mineral composition to conduct research on how and why space exploration and mining will unfold in the future.

“The idea is to create a research effort focused on space and space-related topics that are broader than what NASA does.”

That regolith contributes to understanding how the universe formed billions of years ago. But in partnership with Microsoft, FSI is mining data from the past four decades that was gathered but never analyzed at the Arecibo Observatory. “Arecibo found the first pulsar ever identified,” he says. “But we have three to four petabytes [equal to three to four million gigabytes] gathered by the observatory that has never been analyzed. We now have the heuristics to understand this—and we might identify other, older pulsars.”

This is the kind of thing that excites students, both at the collegiate and postgraduate levels, but also those in high school. That includes two hundred students from Puerto Rico in the STAR (STEAM Teaching at Arecibo) Space & Planetary Sciences program who compete to visit the Institute as part of their studies.

FSI also intentionally endeavors to have one of the largest groups of female space scientists in the world. Already there are thirty women, about a third of the total, working in various capacities and programs. For example, one is a medical doctor teamed with a medical student, also female, to work on health issues associated with long-duration space flight.

So while some of the work Lugo’s people conduct at FSI includes looking out for rocks hurtling toward the earth, much more of what they do is about earthlings hurtling out to space—which is something that wouldn’t happen but for the funding and the organization to support it.

What’s the Dirt?

Space regolith—dust and loose detritus found on the moon, Mars, and other planets—might one day play a role in extraterrestrial agriculture. This is why the Exolith Lab, a wholly owned partner of the Florida Space Institute, develops facsimile regolith for experimentation sold to commercial and educational institutions.

Growing food on other moons and planets might one day enable better, healthier space exploration. The natural soil on those planets will likely need supplementation and figuring out how to do that starts with understanding what is there to begin with.

FSI’s Ray Lugo says Exolith has developed more than one hundred varieties of regolith simulants to meet specific requirements of locations.

Related Links

Mariely Bandas-Franzetti Is Working to Reach Latinas in STEM