|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

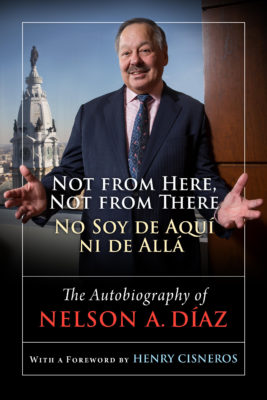

In today’s political climate, Nelson A. Díaz understands the need for diverse stories of adversity and triumph among the Latino community. In Not from Here, Not from There/ No soy de aquí, ni de allá, Díaz tells such a story in recounting his incredible life, beginning with his upbringing in West Harlem’s Puerto Rican community, where he first decided he would “do something.”

His early days of squalor and crime—where his heroes were local gang leaders—led to a pivotal moment as an altar boy where he mounted his own “public-relations campaign,” which eventually led to his admission into the Temple University Beasley School of Law, where he became the first Puerto Rican to graduate.

By understanding his monumental beginnings, it is not surprising to learn Díaz never lost his drive: he became the first Latino lawyer in Pennsylvania, was appointed general counsel for the US Department of Housing and Urban Development during the Clinton administration, then a partner in a top-100 law firm. Díaz went on to become the first Latino judge in Pennsylvania and in 2015 he campaigned to become Philadelphia’s first Latino Mayor.

“I may have been the first, but I did not want to be the last,” Díaz says of his “pioneer” status as a Latino in the upper echelons of the legal field.

Díaz may have carved his own path, but he never fit the mold of an American—nor a Puerto Rican, hence the title of his autobiography. At one point in his youth, he was illiterate in both English and Spanish, creating a division in his life where he was discriminated in New York City for being Puerto Rican and discriminated in Puerto Rico for being American.

“After I ran for mayor, I realized that many stories have not been told about the migration of the Puerto Rican community,” Díaz says. “Nobody has written the story about the impact of this community, either in Philadelphia or in the region, and so it would be important for somebody to let us know what happened here. I wrote it so that I could motivate others to also write the stories about our communities.”

Díaz is changing the narrative of Latino-Americans to be more than just diversity candidates––sharing his story of success to inspire those around him, to remind his community that no one stands alone.

Stories like these take time. Three years to be exact, in Díaz’s case. When writing Not from Here, Not from There/ No soy de aquí ni de allá,Díaz spent the entirety of 2015 fleshing out twelve chapters, recounting his memories with turbulence and elation. The following year was spent with an editor rewriting each chapter.

By October 2017, Díaz handed over his manuscript to his alma mater’s publishing house, Temple University Press, who then published it in 2018. He hopes his story will also restructure collegiate academia, starting with Temple University.

“There are some Latin-American studies that are going to adapt [Not from Here, Not from There/ No soy de aquí ni de allá] to their classes,” he says. “It has the history of people who have not been recognized in our lifetime who have made major, major contributions.”

Díaz even contemplates teaching at his alma mater, specifically offering courses on the contribution of Latinos to the civil rights of America. Breaking the narrative of a one-size-fits-all community is Díaz’s goal: he wants students of diverse backgrounds to compete, to have opportunity, and to restructure that mold. His autobiography is a conversation starter, a vehicle transporting Latinos to their version of the American dream.

“It is the American story that needs to be told of how we Latinos have to struggle and how we are not accepted in our homeland once we come to America, and as a result of that struggle we’re able to make major contributions both to our land and to our country,” he says.

To only boast of his accomplishments would not be telling his full story. Díaz is changing the narrative of Latino-Americans to be more than just diversity candidates—sharing his story of success to inspire those around him, to remind his community that no one stands alone.

“No matter what happened to me, or what I inflicted on myself—I always had someone there to pick me up,” Díaz recalls. “I had great intervention by my community that helped me really believe that through my faith I could do anything, and nothing was impossible. And I believed it. So here I am, still believing that there’s nothing impossible.”