|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Rose Chávez is eighty-two years old, but she still remembers exactly what it was like growing up in her childhood home in La Espora in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her mother was constantly offering earthly wisdom in the form of dichos(sayings), mariachi music blared as the family did household chores, and the smell of corn tortillas was always wafting through the house.

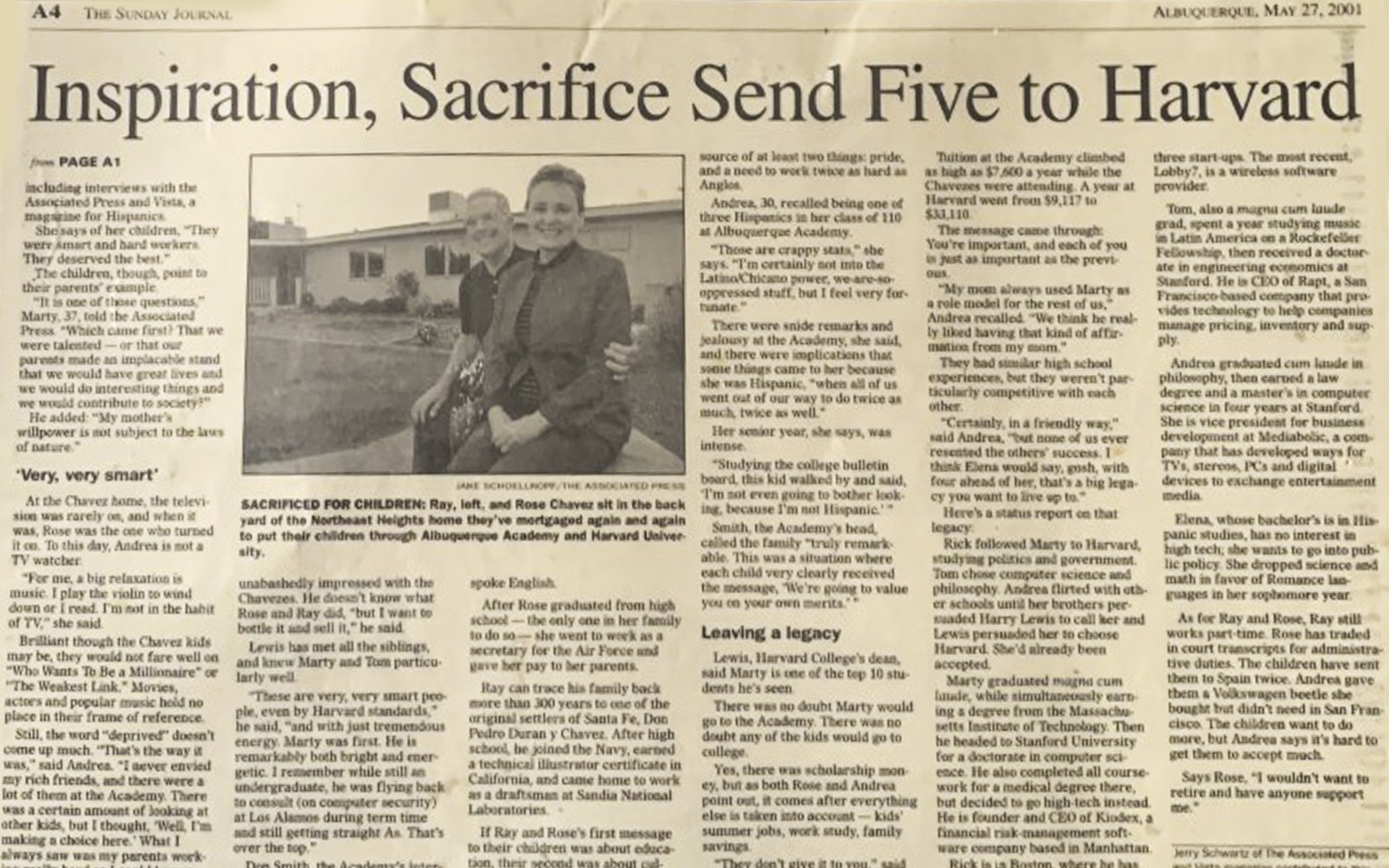

Since then, Chávez has grown up and raised five successful children of her own (all Harvard-educated) alongside husband Ray Chávez. She credits her parents with inspiring her to work hard and fulfill her own version of the American dream.

“My parents had a lot of influence on me—my mother had a dicho for everything, and I’m forever quoting her to this day. She always talked about the value of education, and that stuck with me. So, when our kids came along, Ray and I worked together, doing the best we could for them,” she says.

Past media coverage of the Chávez family has centered on the financial sacrifices the couple made to enable their children’s schooling—scrimping, foregoing vacations, and taking out a second mortgage—or their children’s successful careers, but few stories have focused on Rose and Ray’s personal journey. The couple met at a dance in 1960 and married a year later. As parents, they drilled a love for learning into their children, kept closets full of books, and encouraged the kids to play musical instruments.

The youngest of ten siblings—Ray was the last of eleven—Rose grew up in a strict but loving Catholic household, where the children spoke Spanish, listened to mariachi and Spanish jotas, and lived by the motto of “God, family, and education.”

“It was hard to be poor. Our house had a woodburning furnace and an outhouse, and both my parents worked very hard. We always prayed together,” Chávez reflects. “We were happy and proud of our culture; we always celebrated Mexican holidays.”

To understand Chávez’s life today, you must travel back in time to 1915 when her mother, Spanish-born Julia Araiz Erro, boarded the La Touraine liner at Bordeaux, France, with over a thousand other passengers, passed customs at Ellis Island, and settled in the United States for good. Chávez keeps her mother’s now yellowed passenger record, which mistakenly registered her as Julia Florentino, her brother’s first name.

Araiz Erro—then a wide-eyed seventeen-year-old from Metauten, Navarra—moved to New Mexico, where she met her future husband, Julián Márquez, a handsome immigrant from Jalisco, Mexico.

“They met at the Alvarado Hotel, where my dad waited tables and my mom worked at a coat-check counter. Later, my father worked for the AT&SF Railroad by day and as a watchman by night because it took two jobs to support a big family,” Chávez recalls.

Most people have a pivotal moment that shapes their path. For Chávez, it happened when her family moved to a roomy adobe house: shortly thereafter, the city built a sewage disposal plant behind their family home. The motors would shake the house and a terrible stench would follow, and yet the city council refused to listen to their outcries.

“We felt unseen and unheard and that made me angry . . . I felt bad for my parents. They worked hard all their lives and it was unfair for us to live there,” Chávez says, her frustration pouring out. Chávez’s mother was later widowed, and she then sold the house and bought another one nearby one of her other daughters.

In the 1950s and 1960s, many children from low-income families dropped out of school to join the military or to work and help pay the bills. In the Márquez household, Chávez was the only one to finish high school: she learned court transcription at a night school, while her three brothers joined the service.

After graduating from high school in 1957—she was top of her class in typing, shorthand, and other office skills—Chávez took a job as a secretary at the Kirtland Air Force Base to help her parents. She remained in that role for fifteen years, in between having children, and she did transcription work for a decade before joining Sandia National Laboratories as a secretary for eighteen years.

She retired from Sandia in 2003, but Chávez wasn’t done yet. She and Ray, who had retired from the same lab in 1993 after thirty-three years as a technical illustrator, set up a namesake transcription business and worked for the district attorney’s office and the district court until the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Now fully retired, Chávez continues to advocate for her children, and visits them and their families regularly in San Francisco and New York.

To all the women out there seeking to balance work and parenthood, Chávez offers this advice: lead by example, spend time with your children, limit TV and the internet, and “Keep lots of books around the house. Education is important.”

Chávez and her husband will celebrate their sixty-first wedding anniversary on September 2, surrounded by their five children and eleven grandchildren. Asked about her plans, Chávez laughs and says she’ll remind her grandchildren of her favorite dichos—she keeps a list at home—and that she hopes to instill in them the fighting spirit that allowed her to find her voice and her piece of the American dream.