It wasn’t until Raul Rodriguez moved to Chicago that he began to view race as a barrier firsthand. He had come to attend law school at DePaul University, and he lived in a dorm. There, he noticed a subtle vibe from some of the other Hispanic students. “I think they isolated themselves in some ways,” he remembers. “Almost [like] they felt they came from a world different than the rest of the students. And that of course is a product of being in the minority.”

But growing up in Miami, the opposite was true for Rodriguez. “I never thought twice about it,” says Rodriguez, of the well-integrated city where he grew up. “In Miami, you never think your race could hold you back. But up here, I could tell the community sort of felt that it can.”

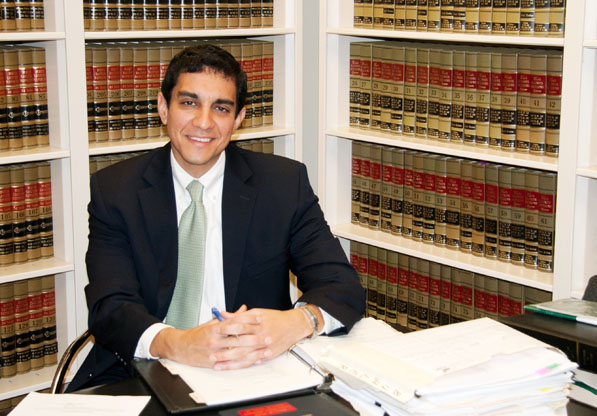

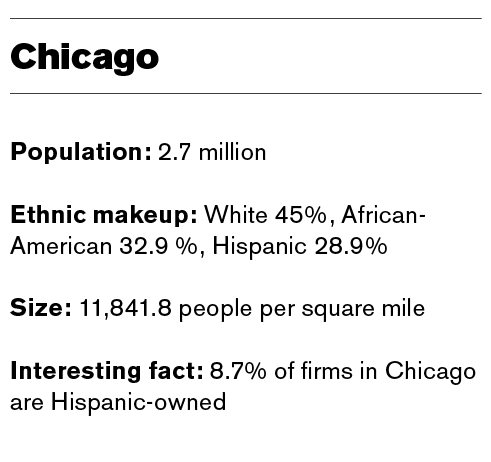

As of the 2010 Census, 70 percent of Miami’s population self-identified as having Hispanic heritage. In Chicago, the number is much less: around 25 percent. Of that figure, many have a blue-collar background. Rodriguez, now a personal-injury attorney at Goldberg Weisman Cairo (GWC) in Chicago, has made a specific effort over the years to reach an underserved Latino community. “The firm was looking for help, and it was a good fit,” Rodriguez says. “In the Hispanic community, no one cares about your pedigree as a lawyer. It’s a tight-knit, family-centric atmosphere and what matters is whether you can relate.”

Rodriguez can, of course. The son of an Ecuadorian father and a Cuban mother, he grew up with all of the Latin culture of South Beach, Miami. Before he began at GWC, the firm had undertaken initiatives at the Father Gary Graf Center, an immigration and social-services program in Waukegan, Illinois. But they wanted to expand their presence in the community. Rodriguez has since worked closely with the Mexican Consulate, which has opened many doors to other parts of the community, including the often hard-to-crack realm of union labor. “In Chicago, a lot of the Latino population is working class,” Rodriguez explains. “And sometimes the thing they need to hear most is, ‘You can make it. The world isn’t closed to you.’”A lot of the message also comes down to a simple education on workers’ rights. “A surprising amount of employers rely on fear to manipulate their workers,” Rodriguez says. “If someone does get injured, they’ll lure them with the promise of friendship or threaten to fire the person.

I’m not anti-management by any means, but the current system can create a huge gulf between management and labor. It’s always sad when you see someone with a really bad injury, and the boss is at fault, but he says he’ll protect them if they don’t take legal action, then fires them.”That managerial bent toward self-preservation has characterized several of Rodriguez’s cases, including one of his proudest victories. While on the job, a diabetic bus driver slipped down a flight of stairs and broke her ankle, but the employers refused to pay workers’ compensation because they deemed the employee to “not be in the course of employ.”Though others counseled the bus driver that pursuing legal action wasn’t worth it, Rodriguez saw an injustice that needed to be righted. Thanks to a keen legal understanding and tireless effort, he was able to win the case on appeal.

It’s an intriguing duel: On one side, a company with plenty of resources. On the other, a lone employee. Both trying to get an edge through the legal system. “The best thing workers can do is arm themselves,” Rodriguez says. “The company is going to have an army of attorneys behind them, and workers need to have a chance to protect themselves.”

Rodriguez says he became a lawyer—the first in his family in the United States—so he could stand up for inequality. So he could fight for the little guy. “It was the idea of creating change, affecting society for the better as an attorney,” he says. “Not to mention that it creates a lot of power in society that you can use for good.”

And has he? “I feel like we do the best we can within the system,” Rodriguez qualifies his answer, explaining that if it were up to him, the foundations of the management-employee system would look a little different. “I think about this a lot. If we would just treat workers as assets instead of expenses, I think it would really help labor in this country. They’re not the enemy.”