Foreign investors poured $182 billion into Latin America and the Caribbean in 2013. Central America, South America, and the Caribbean promise economic opportunities in a number of industries from extraction to automotive manufacturing to agriculture. And an emerging middle class stands to capture the attention of consumer brands from every sector.

“Latin America, in terms of gross national product, is similar to China,” noted of Mexichem chairman Juan Pablo Del Valle Perochena in a publication by FTI Consulting. Latin America and the Caribbean’s 260 million people account for a $3.6 trillion gross domestic product (GDP) annually. “Within 10 years we’ll have 350 million people . . . making an additional $3.8 trillion of GDP,” he continued. “If that growth doesn’t excite businessmen and entrepreneurs, what does?”

From 50,000 feet, Latin America looks like an investor’s playground, but it’s in the absence of a deep dive that interested parties find themselves hacked, sabotaged, or played. The environment is one in which opportunity and potential are counterbalanced by corruption and crime. For more than three decades, global business advisory firm FTI Consulting has been helping businesses assess and mitigate the risks of doing business around the globe. In Miami, Arnold Castillo leads the Latin American team as it investigates, strategizes, and partners with businesses to ensure their operations run safely and efficiently.

Castillo grew up in Peru, cut his teeth in the Lima Stock Exchange (BVL), and facilitated the privatization of the country’s national railroad. Having also worked at top risk consulting and management firm Kroll, Castillo leads regional services from Miami with an insider’s knowledge. Despite its 32-year history and 18 years as the only publicly traded risk consultancy firm, Castillo says only in the last decade have businesses started to use FTI Consulting’s services proactively. Much of the work he does is still reactionary—after the firewall has been breached or the assets lost.

One of the biggest contributions to the foreign investment that Central America saw in 2013 was the completed acquisition of Mexican brewery Grupo Modelo by Anheuser-Busch InBev. Similarly, mergers and acquisitions in the banking and electricity industries fueled an eight percent surge in foreign direct investment in Colombia last year. Such activity has already proved lucrative, but market entry, says Castillo, requires a methodical evaluation to go off without a hitch. There are several relevant issues to consider when looking for a local partner such as the party’s history of litigation, criminal or regulatory actions, troubled transactions, allegations of corrupt or illegal business practices (domestic and foreign), unreported financial difficulties, misrepresentations of management team qualifications, and undisclosed related-party transactions. Overlooking any of these areas can be materially and publicly damaging for an investor.

For example, a party invested in extraction activities may require construction operations quoted at the outset at $1 billion but, due to collusion, could face a $4 billion completion cost. And even if operations appear smooth on the outside, if trafficking groups become unknowingly involved or illegal business practices are employed to get the job done, the investing party’s hands come out just as red. Foreign investors are rightfully hesitant to trust local resources, especially where trade secrets and business-critical information are involved. “Local resources, especially in very small markets, may switch loyalties or work for competing companies,” says Castillo.

“Long-term capital usually requires a macroeconomic environment that is relatively predictable and stable. Latin America has had long periods of hyperinflation, fiscal irresponsibility, and political instability,” said FTI Consulting’s chairman of Latin America, Frank Holder. Weak institutions, a weak regulatory environment, corruption, and arduous conflict resolution also mar local interactions. “Investors require a fair playing ground,” he continued, “and there we have a lot of work to do.”

FTI Consulting excels in understanding the nuances of the market, including those that can be damaging to business. Using open source records and discreet source inquiries, Castillo and his team peel back the layers of topical due diligence to find issues that a remote investor can miss. With an extensive network of investigative journalists, forensic accountants, and former FBI, CIA, and police agents, the firm offers the best of both worlds: local immersion and trusted integrity.

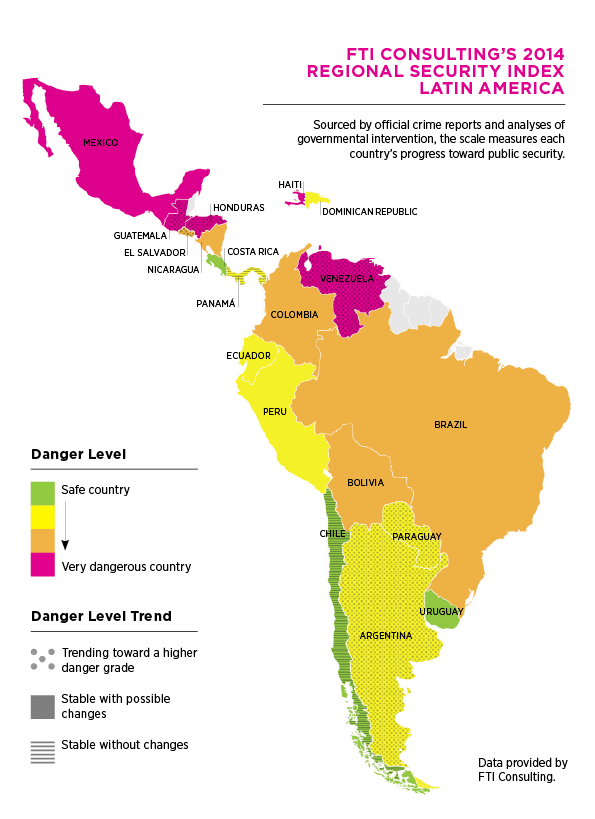

You don’t need to be an insider to recognize the presence of violence and corruption in Latin America and the risk it can pose to business. Read or listen to the news, and it’s a theme that, as FTI Consulting’s chairman of Europe, Middle East, and Africa consulting has said, many Americans associate with the region. “Corruption and security issues are endemic,” says Castillo, which is why FTI Consulting is constantly counseling clients on ways to mitigate danger. In Latin America specifically, organized crime, delinquency, drug trafficking, and guerrilla presence are particularly pervasive. The firm publishes a security index every year, and for the first time in a decade, some countries in Latin America are trending toward safety and stability. But many of the dangers, Castillo says, are not going away, they’re just moving. “When you hit hard on crime,” he says, “it migrates. We were involved in the evolution of Panama, and problems that we didn’t see in [neighboring] Costa Rica two years ago are starting to emerge.”

In Peru, for example, security in the larger cities has declined in the last year, creating a need for crisis management, but the Peruvian government lacks the efficiency to deploy resources. Even in some regions of the country that receive significant royalties from mining operations, funds are not directed toward improving security, infrastructure, or the cultural problems that feed crime and extortion, says Castillo. They end up in networks of local corruption schemes. Similar problems persist in Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia, Venezuela, and the Dominican Republic.

Castillo suggests foreign parties make security their responsibility and not leave it up to federal, state, or local authorities, which can be compromised by crime syndicates or internal corruption. “Most of our clients who rely on government support have lost faith in the system,” he continues. For those clients seeking to take security into their own hands, FTI Consulting strategizes to create rings of protection, beginning with security assessments, audits, and designs of surveillance and electronic security systems, followed by continuity and emergency planning as well as staff training, and rounded out with executive protection. In climates of instability, FTI Consulting is constantly improving its approach to personnel protection. The firm even offers clients and their families courses on prevention and negotiation in the case of abduction.

Illegal activities are not the only impediments to business in the region. Latin America’s culture and history of activism make it conducive to social conflict, which, even when legal, can be disruptive. Communities opposed to a commercial presence can be stirred to action without proper communication, especially if a predator or toxic third party becomes involved and exacerbates tensions. In such cases, FTI Consulting will engage in social monitoring and develop a map of stakeholders. It is critical, says Castillo, to know whose interests are at stake in order to effectively relay the impact and the benefits of operations.

Some threats are not tied to any region or context. “Geographical position is not of interest to hackers or money launderers,” says Castillo. “They look for the most vulnerable institution.” In the aftermath of recently compromised data in the United States retail market, cyber security is on the minds of many executives. It was not always, says Castillo, and the mentality that cyber security is an expense rather than an investment can get companies into trouble. While financial institutions may be obvious targets, the pervasiveness of software as a service makes almost any industry vulnerable to cyber crime. If compromised, an institution may have more than its own assets to worry about. The information of high-profile clients—even government officials—can be at risk. It’s those reputation-damaging breaches that radically shake up the culture of an institution, says Castillo. “The solution,” if institutions are prudent enough to employ it, he says, “is to be savvy about the way they build their compliance programs and frameworks and to have centralized procedures in case of an outage.”

While the risks are serious, FTI Consulting maintains that doing business safely and successfully in Latin America is entirely possible with the proper due diligence and the right partners. “Our presence has been more in demand because of the challenges to security conditions in Latin America,” says Castillo, but “what drives our presence is trust.”