|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Did you ever meet someone and get the feeling you already knew them?

I’ve never met R. Martin (Marty) Chavez—at least, not beyond an hour-long interview conducted via Zoom. Yet, in a sense, I’ve known the man most of my life.

That is, I’ve known of him and his family, and while we haven’t traveled similar roads, we do have similar backgrounds.

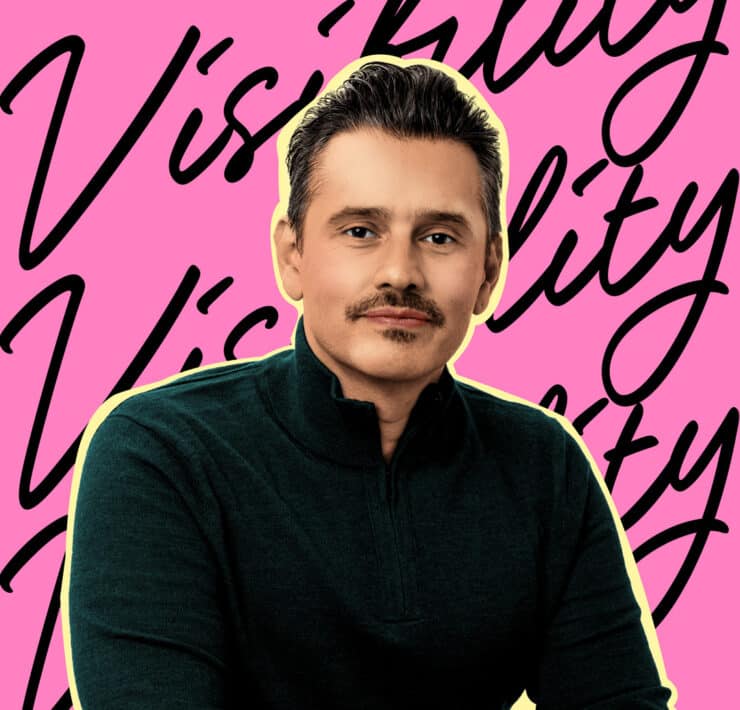

Still, before we spoke, it took me a minute to piece together that the “Marty Chavez” I was supposed to interview later that day—the fifty-seven-year-old investment banker, Silicon Valley tech entrepreneur, and former chief information officer and chief financial officer at Goldman Sachs—was the same Martin Chavez whose early claim to fame was being first in line in a family that’s likely considered Mexican American royalty at Harvard.

For Chavez—whose family roots in New Mexico date back to the founding of Santa Fe in 1610—a childhood spent in Albuquerque revolved around three entities that were both powerful and sacred: family, church, and education.

“There’s a little family legend that I think says a lot. My mom’s from the barrio—Barelas [Albuquerque]—definitely the other side of the railroad tracks. When she was ten, so the story goes, she vowed to either A, be a nun, or B, have ten children and send them all to Harvard. She chose B,” Chavez says, “and she’s a ruthless grader and has high standards. She gives herself a 50 percent score for having had five, not ten children. But she did send them all to Harvard.”

That’s right. Five Chavez kids. All Harvard graduates. Marty was the first Chavez to graduate from the prestigious university, followed by his siblings Rick, Tom, Andrea, and Elena.

I graduated with Tom in 1990. I was friends with Andrea, who was a freshman when I was a senior. Ten years later, when I returned to Cambridge to attend the John F. Kennedy School of Government, I met Elena, who was then a senior.

Owing to Camelot lore, you might assume that well-to-do families such as the Kennedys of Massachusetts would hold the record for the most Harvard graduates. But, according to Marty, a dean actually did the research and confirmed that la familia Chavez de New Mexico holds the distinction of having one of the largest groups of siblings in a single generation attend the university.

A few years ago, Marty was elected by other alumni to the Harvard Board of Overseers. How could he lose? He had four votes right out of the gate. This year, he serves as president of the board.

This version of the American Dream is brought to us—at least, in part—by a lot of sweat, scrimping, and saving by Rose and Ray Chavez. Along with Catholicism, the gospel of higher education was like a second religion to the Chavez family. Even when money was tight, the Harvard term bill got paid on time.

At Harvard, Chavez pursued—concurrently—a bachelor’s degree in biochemical sciences and a master’s in computer science. Then he was off to Stanford to pursue a PhD in medical-information sciences.

But all the while, Chavez had yet to admit to a personal truth: that he was a gay man.

“I can tell you the exact day when I came out,” he says. “It was in 1988, and I was a PhD student at Stanford. I had told myself that the day I successfully defended my dissertation, I was going to come screaming out of the closet. So, I literally went from the defense of my dissertation to a meeting of the gay and lesbian alliance at Stanford.”

He was twenty-four years old. Of course, Chavez knew who he was long before that.

“Four years old,” he says. “I was 100 percent certain at the age of four.”

“I really think it was my Hispanic identity and my ability to speak Spanish that made it possible, which I only had because my mother insisted on it.”

Now, I’m curious about something else. How old was he when he became Hispanic?

He chuckles, knowing immediately what I mean. I want to know at at what age he started identifying as Hispanic.

“The school I went to was mostly white, and the city I lived in was overwhelmingly Mexican. So, I wouldn’t say I had this identity of being Hispanic—I had this identity of being an oddball and knowing I didn’t quite match up,” he says. “I became Hispanic when I was sixteen. I had just gotten into Harvard, MIT, Caltech, and Stanford. One of my dad’s colleagues asked, ‘Which schools did Marty get into?’ My dad said, ‘He got into those four, and he’s going to Harvard,’ and this man said to my dad, ‘My daughter would’ve gotten into Harvard too, but she didn’t have the right last name.’”

I know this story. I’ve lived a version of it. It’s a slam on affirmative action, an implication that if Chavez hadn’t been Mexican American, he wouldn’t have gotten into such prestigious universities.

But Chavez does not owe his success to his name or any other such superficial identifier. After moving to Palo Alto to attend graduate school, Chavez cofounded Quorum Software Systems in 1989. He served as the cloud technology start-up’s chief technology officer until 1993, when he went to New York to work for Goldman Sachs. There, he built a career by using data, mathematics, software, and computers to solve complex problems for clients. He served as chief information officer, chief financial officer, and eventually global cohead of the financial giant’s securities division.

I joke to Marty that, taking nothing away from all his hard work, it’s obvious that he and his siblings won the lottery at birth. From what he says, given the fierce support and determination of his parents, it would have been hard not to be successful.

“Totally,” he says. “There’s a certain group of people that you find in Silicon Valley—you find them elsewhere, too—who say, ‘I am self-made. I did it all.’ Maybe that’s true for them. But for me, that would be the most preposterous thought. I worked very hard. But thank God for my parents, because they made it all possible. They stretched and sacrificed. We were always one step ahead of the creditors, just barely, because they were always paying for schools that they absolutely had no business sending their kids to, schools that they couldn’t afford.”

Hard work. Excellence. No excuses. If you want to know the secret to success in America, that’s a good start. The best parents, I’ve learned, are not hands off.

“There’s a story I love telling,” Chavez offers. “I took sophomore standing at Harvard. I applied for special permission to take five courses, and they were mostly graduate courses. Then, the grades get sent home, and I got four As and an A-. And my mom pointed at the A- and said, ‘What happened here?’”

In Chavez’s case, he was also helped by the fact that, early in life, he found his jam: numbers.

“I was really good in math,” he says. “My parents figured out very early on from the teachers at school that I was remarkably, sort of weirdly good at math.”

Good enough to skip sixth grade entirely. Good enough to take calculus at the University of New Mexico before he reached puberty. And that math class at the university changed everything: it was there that Marty discovered what was—in the mid 1970s—a newfangled contraption: the computer.

This hot little item, Ray Chavez told his eldest son, was the future. In a scene that Marty describes as reminiscent of the scene in The Graduate where Benjamin Braddock is pulled aside at a party and given a piece of advice about where the future is headed, his father—who worked as a technical illustrator at Sandia National Laboratories—pulled him aside one day when he was just twelve years old. He told him, “Martin, the future is computers.” The year was 1976.

His mother, Rose Chavez, also had advice for her children.

“When I was a kid, she would say, ‘Your Spanish is going to be important for your business. I insist that you learn Spanish and that you study it properly,’” Chavez recalls. “And I’d say, ‘Mom, I’m a computer scientist. What does it have to do with Spanish?’

“As with most things,” he continues with a laugh, “she was right. She saw it much more than I did, this future where I could bring it all together.”

That future that Rose Chavez envisioned was finally realized years later during what Chavez calls a “formative moment” in his nearly twenty-year career at Goldman-Sachs.

“One day, the partner who ran the commodity business walks by my desk, and he says, ‘So, Marty, someone told me you speak Spanish.’ I said, ‘Well, did you ever have a look at my last name and consider that maybe I speak Spanish?’ And he said, ‘That’s awesome. All these years, I just thought you were Jewish.’ I don’t know why he thought that. Maybe because we were at Goldman Sachs, and I’ve always hung out with the Jewish kids,” muses Chavez, whose father is descended from a long line of Spanish Jews. “Then, he said, ‘I need you to go to Buenos Aires on Monday and talk to a bunch of Latin American oil company executives.’”

Chavez’s experience in Argentina was transformative. And because of it, his employer began to see in him a new Marty.

“Suddenly, I went from being a computer scientist, doing lots of math and software on the trading desk, to [being] in the world and building relationships with clients,” he says. “My edge was that I spoke Spanish—a lot of business was coming from Latin America, and I went on to do a bunch of things at Goldman.”

“I had told myself that the day I successfully defended my dissertation, I was going to come screaming out of the closet. So, I literally went from the defense of my dissertation to a meeting of the gay and lesbian alliance at Stanford.”

Naturally, Chavez gives away all the credit for his big break.

“I really think it was my Hispanic identity and my ability to speak Spanish that made it possible, which I only had because my mother insisted on it,” he says.

By the end of his tenure at Goldman Sachs, Chavez had become the highest-ranking Hispanic and openly gay executive on Wall Street. Determined to not be the last of either, he was also a leading member of the firm’s Hispanic/Latino and LGBTQ+ networks.

As of September 2019, Chavez is retired—not in the conventional sense, of course. He continues to serve Goldman Sachs as a senior director. He has also accepted positions as vice chairman and partner at investment firm Sixth Street Partners and as a board member for international financial services company Grupo Santander, among a variety of other organizations. And of course, Chavez will keep dreaming, building, and investing. His expertise will always be in demand, as will his energy. Indeed, Chavez needs plenty of energy to keep up with his two children: Sebastian, six, and Penelope, four.

This son of Albuquerque is proud of who he is—a partner, brother, father, and son. A gay man. A Latino. And a financial industry insider who spent decades as a whiz on Wall Street.

But he’s also more than that—and less. The really impressive part is that, most of the time, he’s just Marty. And he wouldn’t have it any other way.

The Potential in Intersections

“I’ve never wanted to pigeonhole myself as a banker or computer scientist. I’ve always wanted to explore and develop the intersections: what happens when software eats finance, or when life becomes programmable? There’s so much whitespace—so many blank canvases and so many possibilities—at the intersections. I expect my next twenty-five years to be at least as busy as the last twenty-five . . . paying forward the coaching, mentorship, and sponsorship I’ve received along the way.”