Senior vice president of C.D. Peacock, Aida Alvarez, charts her career with road maps. She left her last job because she reached her destination—having grown Birks and Mayors Jewelers in Florida to more than 50 stores—and needed a new challenge. Now she mentors other women to forge a plan for success, even as she embarks on her next journey: to become president and CEO.

As a Latina, you are a minority in two ways in the luxury watch and jewelry industry. What has it been like to rise to an executive level in that climate?

Because my expertise is in watches, I work in an arena dominated by men who are used to dealing with other men. It fascinates me how men sometimes speak differently to women executives in the industry, as though we’re not decision makers. It’s a true phenomenon. I look people in the eyes when I speak to them, and if they don’t look at me, I know they don’t see me as an equal. There are times, even now, when I am in meetings with my boss, who is the president, and other men will direct all the questions to him. He replies, “she is the decision maker.” It’s great that he has that respect for me.

How do you deal with that dynamic and maintain your composure? Does it ever deter you?

I just know those men won’t get far if they don’t respect me. I’ve taught myself a lot about watches to the point where I can sit and talk to an actual watchmaker. When I negotiate with a vendor, I can say with confidence that I have a customer for their product. I have always displayed confidence in my knowledge and skill, and that type of confidence is what I try to impart to others looking to rise in this industry.

Milestone Jewelry

When Aida Alvarez first became a watch buyer in Miami, she spent a lot of time sitting in traffic on congested Florida highways. Searching for a distraction, she often looked up, imagining the canvas on which she would plaster the campaign for Rolex’s number one selling watch. “No one had ever advertised Rolex on a billboard,” recalls Alvarez, now more than a decade later in her Oak Brook, Illinois office. “No one thought it could be done.”

When Alvarez proposed the idea, the response from Geneva, Switzerland (Rolex’s headquarters) was a swift and resounding “No.” Rolex is a luxury brand, and billboards don’t exactly evoke luxury. As at many points in her career, Alvarez did not allow herself to be deterred. After much persistence, in 1994, the first Rolex marketed to commuters was exhibited in its enormity alongside Interstate 95.

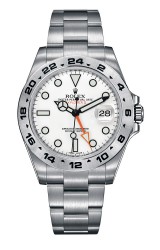

On her wrist, Alvarez wears that very watch, the Rolex Explorer II. Today, the updated version is bigger, and among Alvarez’s collection, it is certainly not the flashiest. But it is a symbol of the milestone that marked her strength in the watch business and the boldness with which she continues to stand out in the industry.

Who believed in you as you were coming up through the ranks in jewelry?

Two people in this industry mentored me: the former president of Rolex, who has since passed away, and the chairman of the most prestigious watch brand in the world, Patek Philippe. When you first join this industry, you go to lots of fancy dinners, and there’s a lot of etiquette to learn. I didn’t know any of that in my 20s, but they took me under their wing. They weren’t going to let me fail.

Was that unusual for such powerful executives to mentor a woman for leadership?

Yes. It still amazes me that I had such an opportunity. They were very forward-thinking in that respect. There’s a club called the 24 Karat Club, the biggest annual industry gala held at New York City’s Waldorf Astoria. It’s like the Academy Awards of jewelry. Historically, women were not allowed upstairs. They were hosted downstairs to show that men led the industry. The first year I was invited I attended with my mentors and said, “I’m not sitting downstairs.” They made a promise: every other year I would sit upstairs with each of them. And I still do. They were able to break that barrier because they represented the two most important brands.

Have you found that as a minority in the industry it has served you better to be connected to your peers or to make your own way?

This is a small industry, and people move around often, so I’ve learned to never burn bridges. My peers and I have all grown up together in jewelry and have become leaders of our respective companies. I am proud to say that we’ve maintained partnerships, which has always been a strength of mine. In 1997, the first woman became president of a watch company. She was strong, someone I looked up to, but she was not generally well-received within the industry. When I was named Woman of the Year, she said I was the one woman she respected because, though we were of few women in a small industry, she and I were not fearful of one another.

What are some of the lessons you learned climbing the corporate ladder as a Latina that you can teach employees?

Right now, I’m mentoring a young woman in whom I see a lot of characteristics of myself at her age. When I was just starting out in this business, I had a lot of ideas and wanted to express them all and share what I could at the table. I learned, however, that sometimes you have to pull back some aspects of yourself. You have to have a plan—both in your day-to-day business and in the long term. I call that a road map.

What did you feel you had to rein in, and how did you harness your ideas?

When you’re coming from a different background, you have to rethink the way you present things because not everyone will understand you. At my previous company, I had three different presidents—a Jewish Israeli man, and Irish-American, and a Frenchman. I thought it was enough to know the Latin market in Miami, where we operated, but they would challenge me and ask how I knew certain things. I had to explain the way Latinos feel, learn, and think. I had to organize those thoughts—and also eliminate some ideas.

How does that mind-set play out in the long term, as you said?

It forces you to be conscious of the way others perceive you, which can inform the way you conduct your business to reach your goals. As a woman, there will be obstacles you must plan for. A lot of them can be overcome with confidence, but you have to first know what you’re working toward on the other side. I did the same thing when I first came to C.D. Peacock. I listed my objectives, and when I revisited them a year later, realized I had achieved 90 percent of what I set out to accomplish. It went by so fast; I hadn’t even stopped to acknowledge it.