Juan Rangel almost missed his calling with Chicago’s 27-year-old United Neighborhood Organization (UNO) three times. He first heard about the group when he was 18 years old. UNO was hosting a community gathering in a church gym to discuss crime in the area and though he thought the work they were doing was admirable, he felt too young to play a part. Rangel did, however, feel inspired by UNO’s urging to get involved in the community, so he nominated himself to serve on the local school council. UNO extended an invitation for him to attend training. He accepted, but got cold feet and stood outside of the building watching other trainees stream in, almost missing his first opportunity to join one of the most influential community-organizing groups in the country. Eventually, he stepped inside and ended up becoming a regular volunteer. Rangel turned down two jobs with UNO before accepting his first position as director of UNO’s Little Village chapter.

Juan Rangel almost missed his calling with Chicago’s 27-year-old United Neighborhood Organization (UNO) three times. He first heard about the group when he was 18 years old. UNO was hosting a community gathering in a church gym to discuss crime in the area and though he thought the work they were doing was admirable, he felt too young to play a part. Rangel did, however, feel inspired by UNO’s urging to get involved in the community, so he nominated himself to serve on the local school council. UNO extended an invitation for him to attend training. He accepted, but got cold feet and stood outside of the building watching other trainees stream in, almost missing his first opportunity to join one of the most influential community-organizing groups in the country. Eventually, he stepped inside and ended up becoming a regular volunteer. Rangel turned down two jobs with UNO before accepting his first position as director of UNO’s Little Village chapter.

“When I first encountered UNO, something really stuck with me: You can simply want change, or you can build power to make change. I didn’t want to be a powerless person,” said Rangel, now CEO of UNO. “I didn’t want to grow old and bitter about the system. What drew me to UNO was their understanding of the world as it is, instead of the world as they’d like it to be. They understood the practicality of the public arena and how to win and succeed in that arena. We’re still very pragmatic in our approach.”

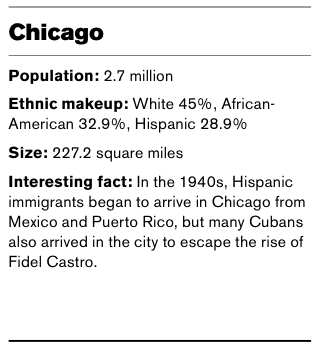

Twenty-two years later, Rangel feels like his work with UNO is just beginning. Since its inception, the organization has challenged Hispanics to play active roles in the development of their communities while leading several important campaigns, from Chicago’s school-reform movement in the 1980s to its naturalization drive in the ’90s, which assisted 65,000 individuals in becoming American citizens. These days, Rangel spends a majority of his time managing UNO’s 11-school charter network that serves 5,500 low-income children, hoping to produce students that will help combat the public perception that they are a “victimized minority group” when he believes Hispanics are the next successful wave of immigrants.

“My parents came to this country from rural Mexico; they crossed the border illegally and made a life here for our family. All nine of us lived in a small attic above an apartment complex. People in the community, like my parents, don’t see themselves as victims. The problem is that public leaders try to portray us as victims in order to fulfill their political goals. If you look at the history of our nation, especially in Chicago, Irish and German immigrants worked hard to get ahead and were never seen as victims,” Rangel said. “I don’t see the community we serve as a ‘challenge.’ Statistically, we serve a high-poverty area, but within this area are people who are family orientated, churchgoing, mostly two-parent households; these are people who have incredible work ethics and entrepreneurial spirits. I see the assets we have as a community, not the challenges that must be overcome.”

“My parents came to this country from rural Mexico; they crossed the border illegally and made a life here for our family. All nine of us lived in a small attic above an apartment complex. People in the community, like my parents, don’t see themselves as victims. The problem is that public leaders try to portray us as victims in order to fulfill their political goals. If you look at the history of our nation, especially in Chicago, Irish and German immigrants worked hard to get ahead and were never seen as victims,” Rangel said. “I don’t see the community we serve as a ‘challenge.’ Statistically, we serve a high-poverty area, but within this area are people who are family orientated, churchgoing, mostly two-parent households; these are people who have incredible work ethics and entrepreneurial spirits. I see the assets we have as a community, not the challenges that must be overcome.”

To combat these negative perceptions, UNO leads by example, developing young Hispanic leaders who are redefining the public arena. Ironically, Rangel also works to combat the misconceptions surrounding nonprofits. The CEO says many young people believe nonprofits are well-intentioned, but offer little room for advancement and require taking a “vow of poverty.” Currently, UNO is operating with a $100 million budget and Rangel hires top talent in various sectors and makes sure they are well compensated because the work they do affects the lives of countless families. Rangel says that while UNO may be a nonprofit, they do not look or act like one, which reminds him of his mother’s philosophy when he was growing up: “Just because we’re poor, doesn’t mean we have to look dirty.” UNO’s charter schools are expertly managed and spotless in appearance. Rather than being characterized as a nonprofit looking for a handout, Rangel sees UNO as business in the nonprofit sector that is investing in the future of this country.

“Many Hispanic immigrants here today thought they would eventually return to their country of origin. It’s tragic that they weren’t able to, but we should encourage them to stay for the long haul,” Rangel said. “We are the new Irish and we have a lot to offer this country. There’s a reason so many people are coming here. The United States is a very generous place. It isn’t an easy place and it offers no guarantees, but it provides opportunity to those willing to work for it.”